Scaling Biology 001: Chris Gibson, Co-Founder and CEO of Recursion Pharmaceuticals

On managing multidisciplinary teams, navigating the public markets, partnership mechanics with NVIDIA and Tempus and the future of spatial biology

Welcome to Decoding Bio, a writing collective focused on the latest scientific advancements, news, and people building at the intersection of tech x bio. If you’d like to connect or collaborate, please shoot us a note here or chat with us on Twitter: @ZahraKhwaja @ameekapadia @ketanyerneni @morgancheatham @pablolubroth @patricksmalone. Happy decoding!

Today we have a special post featuring our guest, Chris Gibson, who sat down with us in Park City, Utah to delve into the details about running a clinical-stage platform company at the intersection of tech and bio. If you’d like to learn more about Recursion, read its feature in our Snapshot here. Let’s dig in!

Given biology and tech are such disparate disciplines, how do you successfully integrate and manage multi-disciplinary teams and ensure that you doesn’t lose the unique strengths of each when working together?

I think this is one of the biggest challenges in the space. When we first started back in 2013, finding people trained at the interface of bio and tech was really rare. One of the things we invested in most was establishing a culture where respect was equal across all disciplines.

In a pharma company, often a biologist or chemist is in charge of every program. In a tech company, it's usually a software engineer or data scientist. In the beginning, we actually valued consensus between teams. It was part of creating an initial set of circumstances where a data scientist and a chemist could disagree, and actually have to work together to move a program forward. It was super messy for the first 50-75 people at Recursion. But I think we got enough biologists and data scientists and chemists and software engineers, to push through the hard part where they actually could learn to speak each other's languages enough that they could have this meaningful exchange, that we seeded a culture where now when we hire people, that is the norm at Recursion.

“…the greatest moat that Recursion had built compared to large pharma was the culture and specifically creating a place where you could bring these two groups together and have them interact constructively.”

When people see it all around them, they transfer [domain knowledge] much more quickly. We had a Chief Digital Officer of one of the top 10 biopharma companies visit Recursion, maybe five years ago, and on his way out the door, he said that the greatest moat that Recursion had built compared to large pharma was the culture and specifically creating a place where you could bring these two groups together and have them interact constructively. I think for all the companies in the space, this is a key lesson, because it's still a competitive advantage compared to the traditional groups and the larger pharma organizations.

Do you have any advice for companies starting out right now? Can they bypass some of the messiness of the first 50 to 70 people? Or do you think that's actually just part of building the culture in and of itself?

I think there's always messiness as part of everything that you build. That's a part of building a company. How do you minimize that, to some degree? I think one thing that can be really helpful is having founders with diverse backgrounds. So when we started Recursion, we had me, a bioengineer. We had Dean Li, who's a physician scientist. And then you have Blake Borgeson, who's an electrical engineer and data scientist. Because the founders already had that messiness together, we created an expectation at the company that this is how things would go. Also, just hiring some people who are fluent in both, like computational biologists. Put a smattering of those on your teams, they can be a bridge to just save you a lot of that messiness.

What was the most difficult challenge you faced thus far at Recursion, and how did you navigate it?

There have been a lot of really difficult things. This is probably true of all founders looking back. We still have a long way to go to achieve our mission and there will be many more difficult things in the future. Maybe I'll share the thing I under-appreciated the most.

The thing that was more difficult than I expected by the biggest amount, was people. When you're in grad school, when you’re working on scientific problems, science has a truth, and your goal is to uncover the truth. There's a beauty in that, an elegance, in trying to uncover that thing, even when it's hard, you know there's a fundamental truth and your job is to find that.

People have their own truths. And those truths change over time. Right? Somebody can be super dedicated to XYZ, and then there can be some change in their life circumstance, or a whole host of things in their lives, that can change their truth in a very short period of time. I dramatically underestimated how hard things like hiring were, how hard managing is. Especially for technical founders, my advice is, get help and coaching early on and surround yourself with some people who are compelling.

When we were about 80 people, we hired Tina Larson, who's our Chief Operating Officer. She and I have extraordinarily different backgrounds and perspectives, we work really well together. But she just sees every problem from a totally different lens than I do and she's really talented as a leader and a manager. So hiring her was kind of intimidating as a founder. You're like, “I'm gonna hire this person who's been at Genentech for 20 years, and was a global head of Roche and then she's gonna report to me, but I'm gonna ask her to teach me all these things”. It's this weird imposter syndrome for founders. At least that's how I encountered it. When I get calls from founders and they're upset, worried, scared, etc, it is very often people that's the issue. It's not the science. So it is important to invest deeply there.

In your recent partnership with NVIDIA, it was suggested that Recursion may start licensing its models to BioNeMo. Could you explain the mechanics of this partnership? Do you think this model will be the future of the company and significantly change the topline for the company?

Only a few large pharmaceutical companies have senior executives who are willing to make massive investments in our field. Leaders like Aviv Regev, James Sabry, and others at Genentech are prime examples. Alongside Bayer and Sanofi, they are among the few taking substantial risks in the space. But, most large pharma companies are still dabbling, forming tiny partnerships with various companies.

There's an opportunity, I think, for us to tap into a different part of the demand curve. The Genentech team put $150 million upfront and over half a billion in near term execution and data-based milestones plus all the program milestones. That's a huge collaboration. Not every pharma is going to do that. Nor could we support that many huge partnerships.

But are there 10 pharma companies who might spend $10 or $20 million a year with us to get access to portions of our data or our models. They're not willing to do the huge partnership, but they're curious about the space and they see us as a leader. They’ve seen this model with companies like Schrödinger, where pharma licenses its software to use on their own projects and data. So we're working through the mechanics of what that could look like for Recursion.

Nvidia sees biopharma as a largely untapped market in its first innings. They want to place bets on a few of the likely winners to make sure that they can seed their marketplace with the right tools, much like Apple did with its App Store. That’s a little bit of how I can imagine the right platform company not having assets in the future: it is by having some broadly useful marketplace like what they have built at NVIDIA with BioNeMo where companies can provide access to their tools as a service. It doesn’t have to be BioNeMo, there are other marketplaces, but we think it's the one that will take off commercially.

“Nvidia sees biopharma as a largely untapped market at its first inning. They want to place bets on a few of the likely winners to make sure that they can seed their marketplace with the right tools, much like Apple did with its App Store.”

We’re building Valence Portal, out of Valence Labs, which is going to be more for academic non-commercial use, where we're going to have lots of different models. It won't be where Pfizer will go, but it will be maybe where grad students or other folks that are doing lighter-weight work in this space might go.

Could you share some details around Recursion’s technological shift from cell painting to brightfield imaging?

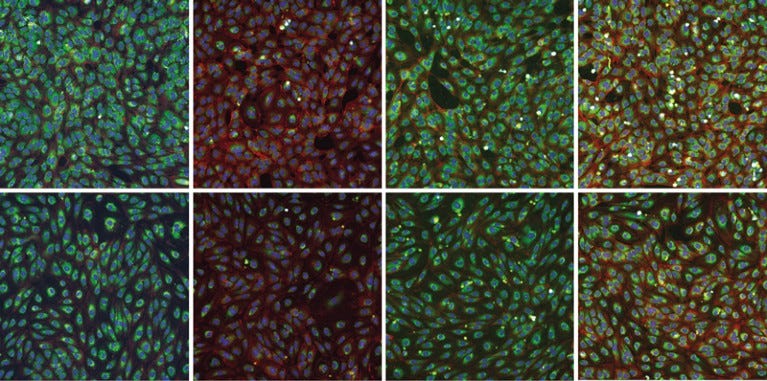

We've been using this technique called cell painting, where we stain cellular organelles across any cell type, to extract morphological features. Members of our team came to me a few years ago and said “we think all the information exists in brightfield data” - just in the light passing through the cell without any stains. I looked at the images, which certainly don’t look like all the information is there, and was doubtful. But it turns out, as we started exploring this and building robust datasets and training models, it's not all the same information, but it's roughly the same quantity of information and roughly the same quality of information. So we were able to train computer vision algorithms on brightfield images that match the performance that we get from the cell painting approach.

That was an amazing turning point for us because what's beautiful about brightfield is that you can do live cell imaging over time, which we think will be really helpful in terms of training causal models. So by the middle of next year, virtually all of our experiments at Recursion will be done this way, where we will be taking multiple time point brightfield imagery. We've also just moved transcriptomics into 1536 well plates, which means we'll be able to extract the transcriptomic signature from the same exact well that we imaged over time using brightfield. Today, at Recursion, when we image, we also do a copy plate that goes for transcriptomics which is a lot more expensive and obviously, from a data perspective, a little bit noisier. So we think this is super, super exciting. This is what we think the future will be multi-modality. It's more data for less cost, which is always what we're driving out of Recursion.

It's interesting because we're moving in this direction now that almost every large pharma company has a cell painting team. Many of them are very good, but I think a lot of them lack the machine learning tools and scale to be able to move fluidly into brightfield. Maybe this is a place for a model that we would put on the BioNeMo, right? You can build a great team at a large pharma company to generate images, brightfield or cell painting. But [it's harder to build a team] to interpret them at scale, especially if you're a large company, who's not putting all of your eggs in this basket. We have billions of images to train our models and most large pharma companies don’t. So we can build models that are going to be much more robust than what they could build, and they could deploy them on their own smaller datasets. This is where we think there's an opportunity from a revenue perspective.

How much do public investors and the stock market affect day-day or company decisions?

I think the theoretical, naive, but idealistic answer is: none. You do what you think is right, as a founder, or a CEO. The truth is that there are tactical limits to how much you can do. And that's true of private companies, too. You just get more feedback every minute of every non-federal holiday weekday about how people think you're doing.

We announced a collaboration with Tempus where we committed to spending $160 million of cash or equity over the next five years. And [on the same day we announced it], it was the second worst day for biotech this year in the market. So everybody was down; we were down. And I feel no differently about that deal than I did when we acquired Cyclic and Valance when we were up 12% on the day. You can’t let the macro-movements of the stock change your perspective or your company will become short term focused and reactive.

Finding a board and a team who can distance themselves from the day to day movements of the stock, and support you because of the fundamental, founding, first-principle beliefs around what you should do is important.

The reality is you do have to understand the market, you have to understand some of the operators that exist, you have to understand hedge funds and short sellers, you have to understand the motivations that exist in various folks. There's these groups that publish these reports, like with Twist and Gingko, and others that got hit by Scorpion, and some of these others. These groups will go and find some things and make them sound way worse than, not always, but often are. And [before publishing the report] they've already taken short positions with a company. There's all of these things I've learned from our CFO, Michael Secora, who was an investor for a decade. Even things like where short sellers get the shares that they sell: who are they borrowing the shares from? Turns out, some very large investors have a policy where they loan their shares to short sellers and some don't. You need to factor that into which institutional groups you try to attract to the cap table.

In the public markets there are these things called 13Fs, where every quarter, large investors, at least mostly US-based large investors, have to report how much of your stock they own at the end of every quarter. Michael wrote a bunch of software to look at all the investors we're talking to, and he scores them on their average hold time, for their high impact bets. So because he has this, you can't know for sure they didn't sell the stock and buy it all back every quarter. But in general, if you see these investors who buy a stock, and they hold it on average for 5 or 10 years, those are investors who are typically very aligned with a big mission, kind of founder-led vision of these companies. You'll also meet these investors who will tell you that [they hold for a long period, but] when you look at the data, their average hold time is under a quarter.

You have to be able to learn this field and study it because there are a lot of people trying to take advantage of first time founders and brilliant scientists. There are also some really incredible people there to support these companies. If you can, distinguish between those two, and really hone in on spending your time with the group of long thought partners, like our biggest shareholders, a group called Baillie Gifford. If you want to be a great investor one day study Baillie Gifford or even Warren Buffett, these people don't buy and sell, or trade. They find conviction in a thing they believe in and stick with it. That's what you have to find as a founder if you're in the public markets and building the future.

Given the skepticism in the market about being a platform vs asset-focused company (at the early stage), do you have any advice for founders on how to walk that tight line on building the company given limited resources?

I think it might be changing. For us, the only way we could raise capital, even from platform-centric [investors], was to demonstrate these meaningful indicators of success by taking programs towards the clinic and now through Phase II. I didn't think we were ever going to have to do that. But it became necessary.

“I think that there may be room in the next couple of years for platform-only companies that don't have assets.”

So even in the context of private markets, this is where sometimes the investor demands can push on founders and execs to make decisions. I guess for us, what we found was at the time we had to build a pipeline in order to have the resources to build the platform. I think that's mostly been the case for platform companies. You even look at platform companies in the public markets, like Schrödinger, who built a software as a service company that's pretty successful. They're also building a pipeline now, even in the public markets. So the currency of the biopharma industry is assets in the clinic. However, I think that there may be room in the next couple of years for platform-only companies that don't have assets. There may be some fatigue from investors with the scale of the investment required to support both so I think there will be more of an opening over the next two or three years for platform companies. If you're a series B company today in this market, I still think you mostly need assets.

Are there any phrases you live by?

I don't know if this is a single phrase I live by but it's close: a lack of a decision is a decision. I often see people who are afraid to make a choice and not choosing is making a choice. My co-founder Blake and I debated a lot about decision making strategies. We were never afraid to decide at Recursion. We don't need all the data to decide except for very limited cases where you can not reverse the decision. In the case where you can reverse the decision, you will gain so much information from just deciding. I see a lot of even founders, especially technical founders, who struggle with [waiting for certainty].

Who has been the biggest inspiration or mentor - what advice or guidance has been most transformational for you?

I think anyone who has been building something in this field likely has dozens of mentors. A few that come to mind for me include our recent dedication and renaming of two of our buildings and one of our laboratories in honor of three mentors. One was Dean Li, my co-founder and dissertation mentor. He's now the equivalent of Merck's CSO. I talk to him every few days, and he continues to mentor me. In some ways, now as a leader at Tech Bio, I think I mentor him in understanding the technology world. We've become partners in that regard. Anne Carpenter at the Broad, who pioneered cell painting, is another. She really championed the whole concept of phenomics, popularized it, and then took a risk on us as a small startup out of Utah. When we sat down with her, we were compelling, and she didn't let the biases against Utah grad student founders hold her back. We also dedicated our chemistry lab to my eighth-grade science teacher, Carol Ponganis, who was instrumental in my pursuit of science. She spent an extraordinary amount of time with me. And then there are my parents, my brother, Tina, and so many others. I think there's probably a correlation between people who recognize they have many mentors and their success. Become a student. Ask for mentorship. Lots of people are willing to give it.

How would you suggest people go about finding such great mentors?

You simply go out into the world and talk to people. When Blake and I met Anne Carpenter, she was already becoming a well-known scientist in the field. At the conferences we attended, she was often the keynote speaker. So, we went to the conferences where she was present and found her during a break. We invited her to dinner to have a conversation with us. Initially, she declined, saying, 'Oh, I'm sorry, I already have plans.' However, a little while later, her plans fell through. She saw us and said, 'Actually, my plans fell through, I'll go grab a bite with you guys.' It's about having the audacity to ask, which happens a lot, I find.

I receive many emails from various founders asking for a lot. Simply asking is not ideal. It's quite different when I encounter someone through a warm connection. Or, I'll be at a conference, and someone will approach me. They won't just say, 'Hey, can you mentor me?' Instead, they'll say, 'Hey, I've been working on this project. I listened to your podcast XYZ. I heard you mention this; can you help?' You can show the level of engagement, like Blake and I did when we met Carpenter. We were like, 'We know every paper you've ever published. We want to discuss the nitty gritty of the science.' It's almost impossible for someone to not spend some time with you. You can earn their mentorship.

Thanks so much for your time Chris this has been extremely insightful.

Did we miss anything? Would you like to contribute to Decoding Bio by writing a guest post? Drop us a note here or chat with us on Twitter: @ameekapadia @ketanyerneni @morgancheatham @pablolubroth @patricksmalone

NB: sentence structure changed in some cases to improve readability.