BioByte 141: Wet Lab Validation of gRNAde, the Role of Gene Syntax in Transcriptional Regulation, and Reasoning from Genes to Phenotypes with PULSAR

Welcome to Decoding Bio’s BioByte: each week our writing collective highlight notable news—from the latest scientific papers to the latest funding rounds—and everything in between. All in one place.

Sonia Landy Sheridan, Artist in the Science Lab (1976)

What we read

Papers

Generative inverse design of RNA structure and function with gRNAde [Joshi et al., bioRxiv, December 2025]

Why it matters: RNA molecules serve not only as carriers of information between DNA and proteins but also orchestrate a range of biochemical functions. Two key challenges in RNA design are the engineering of intricate three-dimensional structures and developing molecules with catalytic function. In this paper, the authors briefly reintroduce the generative RNA design model gRNAde (pronounced like “grenade”), but more importantly, describe impressive wet lab validation results of the pipeline. gRNAde significantly outperforms contemporary physics-based and machine learning tools on pseudoknot design tasks and is also shown to be capable of generating functional RNA polymerase ribozymes with significant sequence diversity from wild type versions. These results show the promise of design methods like gRNAde to help develop an extensive range of RNA machinery.

The last two years have seen a small avalanche of deep learning tools demonstrating impressive performance in protein design and engineering to ultimately develop novel enzymes, therapeutics, and more. Moving one step back in the central dogma, RNA design is also a promising avenue for biotechnology; however, such efforts are challenged by the difficulty of designing the complex three-dimensional structures of RNA and extending that to engineer catalytic function. Specifically, RNA molecules can form pseudoknots which are intricate stem-loop structural motifs formed by complementary base pairing of the single strands. Such features control processes like viral replication but are fundamentally difficult to predict and design. In terms of function, existing computational tools must navigate astronomically large sequence spaces or heavily rely on handpicked heuristics or expensive multiple sequence alignment inputs.

To tackle these challenges, the authors developed gRNAde, a generative language model that uses 3D structural data to learn RNA folding. Briefly, gRNAde begins with a multi-modal structural “prompt” or design specification that can include target secondary structures, backbone coordinates, and additional sequence constraints that must be preserved in the generation process. The crux of the model is a graph neural network module that processes 3D geometric information that can better capture tertiary information, non-canonical pairings, and complex RNA folds compared to previous 2D information representations. gRNAde is also part of a larger design-build-test pipeline; first the model is used to generate a massive library of candidate sequences (approximately 1 million). This step is followed by a screening stage where the RibonanzaNet RNA foundational model “serves a high-throughput computational proxy for experimental characterization by predicting per-nucleotide chemical reactivity profiles and pseudoknotted secondary structure.” Finally, the screened candidates are scored and ranked based on correlation metrics and differences between predicted and true chemical reactivity profiles. This stage narrows down the initial massive library to a small set of candidate sequences that are promising for wet lab validation.

While gRNAde itself was not new as of this paper, the extensive wet lab results were a new, more complete demonstration of the model’s performance and potential. The model was entered in the Enterna OpenKnot Benchmark challenge where the objective was to design sequences for complex pseudoknotted targets across a range of RNA classes like riboswitches, viral elements, ribozymes, and synthetic structures. Crucially, the challenge served as a comparison among various models but also against human experts. The gRNAde pipeline showed impressive performance across the 20 targets of up to 100 nucleotides in length, performing at par with human experts with a 100% success rate on natural RNAs and 90% on synthetic targets. Notably, physics-based methods like Rosetta could only achieve rates of 40% and 70% on the two classes, while RFdiffusion peaked at 80% and 60%. On longer targets (up to 240 nucleotides), gRNAde fell to approximately 70% on both classes (but still in line with human experts) while Rosetta could not be scaled to that length and RFdiffusion could only manage 33% and 50%. Interestingly, gRNAde designs were found to consistently outperform wildtype sequences for natural targets, with the greatest difference being on longer targets (where wildtype sequences had a 0% success rate in part due to the formation of alternate conformations). This indicated that gRNAde was well suited to generate novel sequences for complex target topologies while natural sequences were less optimal due to additional evolutionary pressures. Subsequent analysis showed that the native sequence recovery of gRNAde designs were about 32% while human experts were at 72%, indicating that the model was successfully able to navigate across vast sequence distances to still produce highly correct sequence candidates.

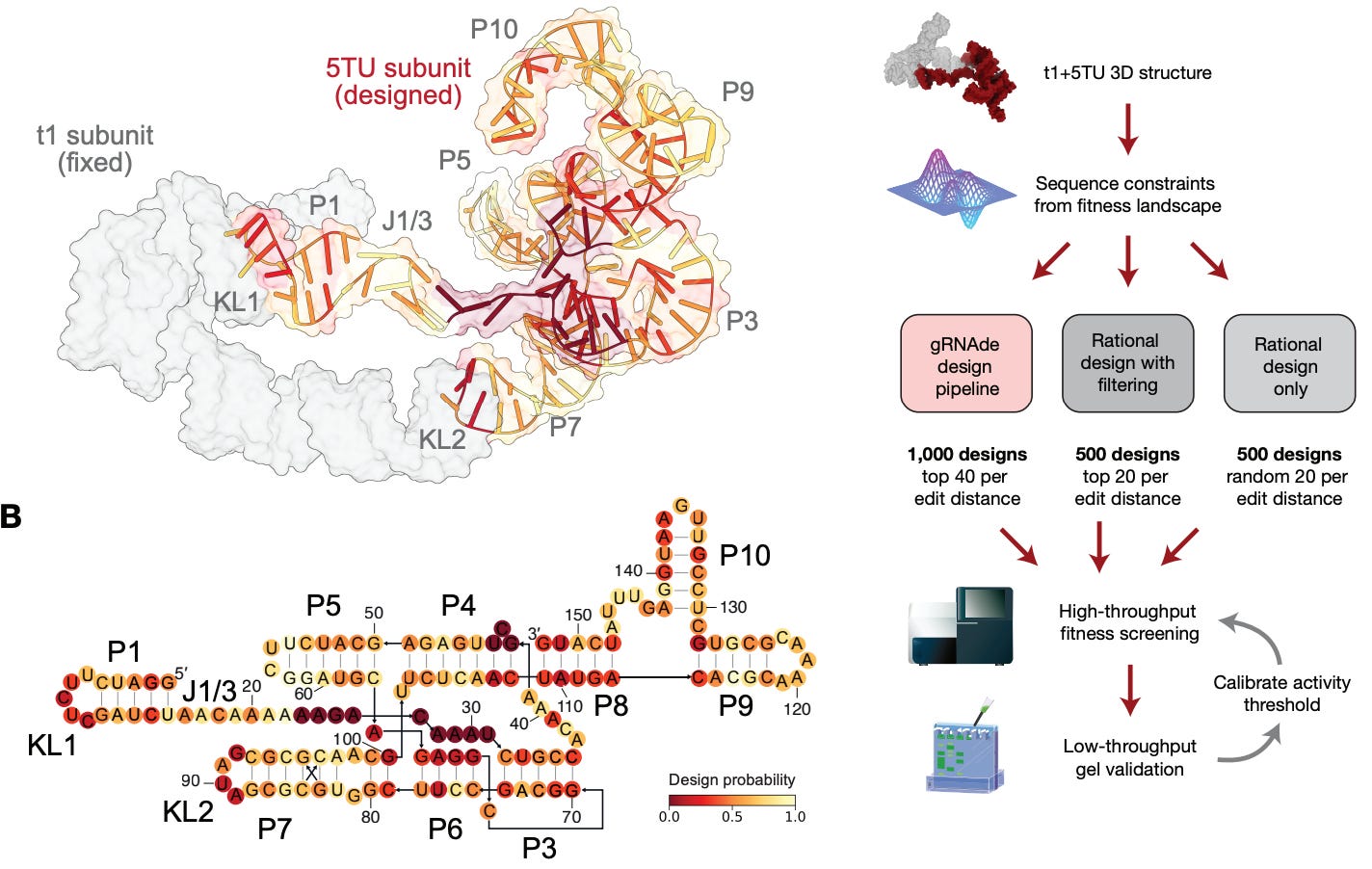

Turning to catalytic function design, the authors applied the gRNAde pipeline to re-engineer the 5TU catalytic subunit of an RNA polymerase ribozyme that models RNA self-replication processes. This target required the preservation of various tertiary contacts and “kissing-loop” interactions that modulate the active site. The pipeline was also adapted to produce functional sequences with mutational distance from known wildtype designs to test the model in sequence space beyond that accessible to directed evolution and rational design approaches. Using a high-throughput sequencing-based assay for validation, gRNAde showed significant performance gains in discovering active ribozyme sequences, with a success rate almost twice that of rational design baselines after filtering the generated library. The authors also noted that gRNAde designs demonstrated higher catalytic activity and superior fitness distributions for designs with up to 30 mutations from the wildtype reference. Comparisons of the generated designs and rational design baselines showed that the former balances mutations across unpaired regions and loops while the latter “mainly mutate[s] canonical base-paired positions while conserving unpaired loops…[which] fails to account for essential tertiary interactions.”

As nice as computational benchmarks may be, the true value of a design tool is in its real world validation, and gRNAde shows impressive results on both structural design tasks and functional design challenges. The model is able to capture the crucial tertiary interactions across various structural elements and can capitalize on that to explore more of the potential sequence space to generate designs that are inaccessible to directed evolution and rational design efforts. The authors point to the potential of gRNAde’s pipeline to help generate, screen, and validate additional sequences to assemble larger structural datasets and drive the development of larger, improved RibonanaNet-like foundational models. Ultimately, the hope is that gRNAde can power the design of novel biological machinery like riboswitches and nanostructures and perhaps therapeutic modalities as well. Hopefully, the influx of new data from techniques like cryo-EM can help bring that vision forward.

Gene syntax defines supercoiling-mediated transcriptional feedback [Johnstone et al., bioRxiv, November 2025]

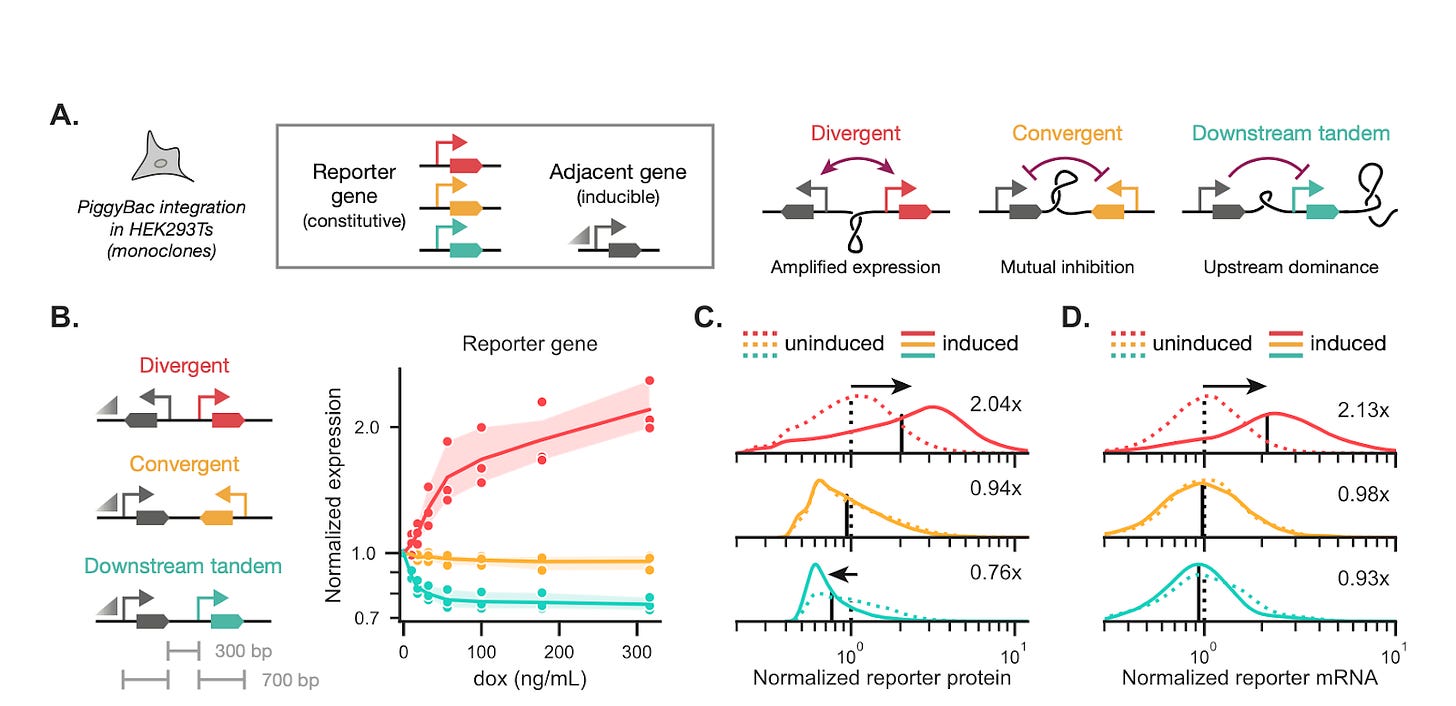

Why it matters: Predictable, high-performance genetic programs are a crucial missing ingredient for reliable cell engineering and scalable biomanufacturing. Johnstone et al. demonstrate that gene syntax – the relative ordering and orientation of adjacent transcriptional units – offers a deterministic design knob. Mechanistically, they show that transcription changes local DNA supercoiling, producing plectonemes – supercoiled DNA loops – that reshape chromatin topology and thus regulate transcriptional bursts. For bioengineers, this illustrates that simple rearrangements of gene order and orientation – without modifying promoters or copy number – can tune mean expression level, stoichiometry, and balance of intrinsic (single-cell expression variance) vs extrinsic (population-level, inter-cell variance) noise.

Using compact two-gene circuits integrated into mammalian cells (HEK293T, human iPSCs) at defined loci (PiggyBac, STRAIGHT-IN landing pads), the authors compared tandem, divergent, and convergent layouts while holding promoters and copy numbers constant. For reference, tandem implies transcription in the same direction, divergent implies units are back-to-back transcribing outward, convergent implies the units face each other – creating a risk of polymerase collision. Genotypes, topology, and dynamics were linked across multiple scales: Region Capture Micro-C (a chromosome conformation assay mapping physical contacts across the locus) showed induction-dependent contact patterns consistent with plectoneme formation, GapRUN (mapping via GapR protein which preferentially binds to overwound DNA) detected positive supercoiling in intergenic regions, and CUT&Tag (antibody-profiling of RNA polymerase II and active histone mark locations) and RNA-seq tracked transcriptional expression and elongation.

Functionally, divergent syntax produced strong positive coupling – the two genes tended to co-burst, yielding correlated expression and a marked reduction in intrinsic noise. By contrast, tandem syntax often displayed upstream dominance: transcription of the upstream gene created positive supercoiling at the downstream promoter and suppressed its initiation, allowing a wide stoichiometric range (weak coupling) useful for decoupling expression. Convergent layouts exhibited more complex or bimodal behaviors, plausibly stemming from polymerase collisions and mixed supercoiling effects. Critically, the team showcases a compelling result: rearranging heavy and light chain genes for an anti-yellow fever monoclonal antibody in HEK293T raised titers ~4x, with downstream-tandem and divergent configurations giving the highest yields. Noise decomposition analyses show syntax controls the intrinsic/extrinsic noise ratio, making noise a programmable feature.

For synthetic biology and biomanufacturing, syntax-aware design translates context-dependence into a predictable engineering parameter: choose divergent for coupled, low-intrinsic-noise expression (useful for stoichiometric complexes) or tandem to decouple and broaden stoichiometric tuning. However, important caveats remain: polymerase readthrough, topoisomerase recruitment, locus-specific chromatin context, and cell-type differences can modulate the effect size. Moreover, some non-monotonic length or distance dependencies point to additional mechanisms beyond supercoiling. To disambiguate the role of syntax, crucial next steps would involve systematic locus/gene library screens and perturbative tests (topoisomerase inhibition, altered polymerase processivity) to establish causality. With further testing, syntax may become a standard, low-cost lever for quantitative biological control – enabling reliable gene circuits and protein production.

PULSAR: a Foundation Model for Multi-scale and Multicellular Biology [Pang et al., bioRxiv, November 2025]

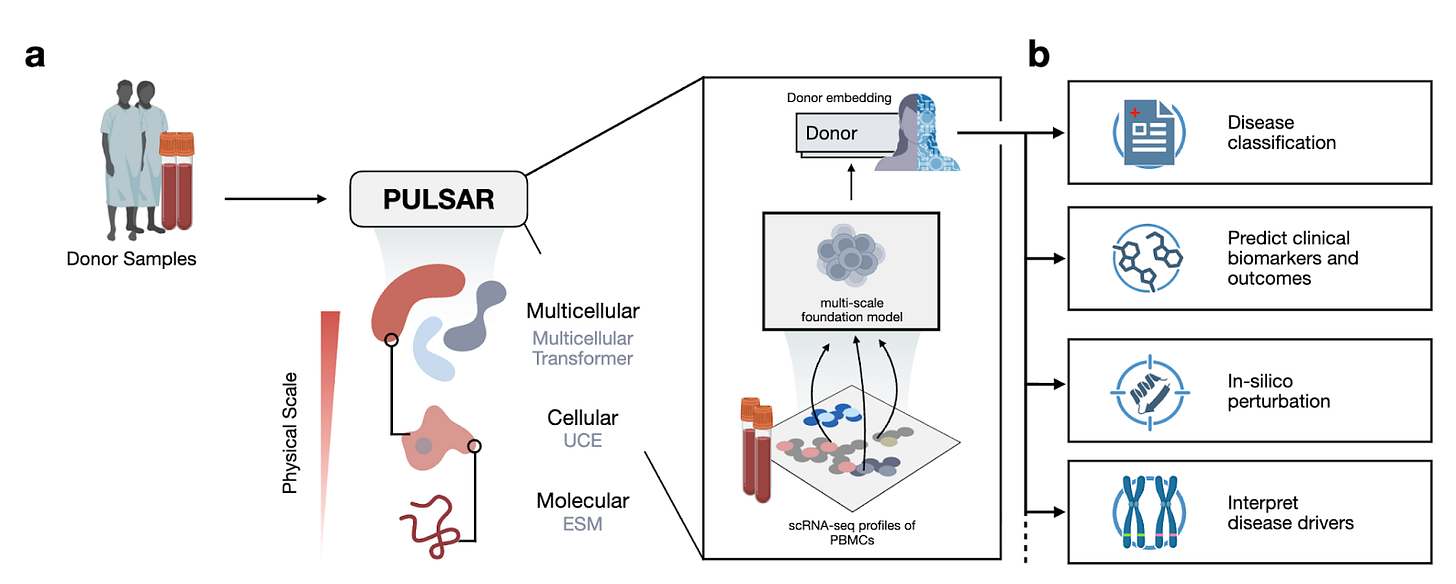

Why it matters: As single-cell sequencing becomes cheaper and more accessible, a rich new source of data is becoming available to mine: patient-specific single-cell profiles. Pang et al. build PULSAR, a model that hierarchically constructs multicellular representations using representations from molecular and cellular foundation models. PULSAR unlocks new insights from this class of data: using it to build rich representations of immune profiles from patient-specific PBMC scRNA data enables new predictiveness across clinical phenotypes such as cytokine perturbations, vaccine responsiveness, and disease classification.

At a high level, the paper is trying to answer the question: how do you build a single model that can reason from genes to cells to whole-patient immune phenotypes, rather than treating each scale in isolation? Most existing models live at one level: molecular FMs over sequences, single-cell FMs over individual cells, or coarse clinical models over bulk measurements. These either ignore the multicellular context (cell/state-only models) or ignore cell-to-cell heterogeneity (bulk and pseudobulk models). PULSAR’s framing is that immune phenotypes are emergent properties of sets of interacting cells in a donor, and that any model that tries to predict clinical outcomes directly from bulk features is missing a helpful inductive bias. Computationally, they formalize this by treating a sample as a bag of cell embeddings and learning a multicellular transformer that aggregates these into a donor embedding, while being grounded in lower-level molecular and cellular foundation models. This lets them exploit abundant single-cell data in a self-supervised way, and then reuse the resulting donor-level representation for a range of downstream tasks (disease classification, proteomics prediction, RA conversion risk, vaccine response, and cytokine perturbation modeling).

In a previous paper from Jure Leskovec’s lab, they build cellular representations (UCE) using molecular representations from ESM2, a protein foundation model. Just like in that paper, in this paper they build hierarchically upon these representations: training a model to build representations of pools of cells (PULSAR) using representations of individual cells in those pools (UCE). One modeling goal here is to be able to model the pool of cells as interactions of individual cells. The encoder takes the UCE embeddings of a subset of cells in the dataset and is trained to predict large parts of the UCE embeddings of other held-out cells. As opposed to bulk RNA-seq (and pseudobulk) methods, this modeling approach aims to explicitly preserve the fact that the populations are mixed bags of unique cells that are interdependent. In the process of this learning objective, PULSAR learns population-level representations, which are used to predict clinical phenotypes as described below.

To make these donor embeddings actually useful, they first pre-train PULSAR on CELLxGENE (36.2M cells from 6,807 donors across 53 tissues and 69 conditions), then perform a second round of pretraining on 8.7M PBMC cells from 2,588 donors to specialize the model to peripheral blood and immune subpopulations. From this, they extract a unified donor embedding and build a reference database, DONOR×EMBED, with 2,804 PBMC donors from 41 studies and ~10M cells, each annotated with disease labels spanning autoimmune disease, infections, cancer, acute and chronic inflammation, and healthy controls. Disease prediction is done in a very simple way: kNN in this embedding space. They also apply a contrastive alignment step on top of PULSAR embeddings using disease labels to sharpen disease separation.

For disease classification, they benchmark against several baselines: (i) the zero-shot PULSAR embeddings without alignment, (ii) a pseudobulk gene expression baseline that collapses cells into a bulk-like profile, (iii) scPoli sample embeddings, and (iv) a cell-type composition baseline that only uses proportions of major immune cell types. PULSAR with contrastive alignment achieves the best overall accuracy (~0.95 within-cohort), outperforming zero-shot PULSAR (~0.92), pseudobulk (~0.89), scPoli (~0.73), and cell-type composition (~0.72), with particularly large gains in macro F1 where class imbalance hurts simpler baselines. They also test on independent external cohorts (different studies, assays, and populations) and show that aligned PULSAR maintains good performance (accuracy ~0.86) while composition-based methods collapse (~0.37), suggesting the donor embedding captures disease-relevant structure that generalizes across batches and cohorts.

For cytokine perturbations, they treat PULSAR as a cross-scale generative model and test whether it can simulate treatment responses. They use a large ex vivo perturbation atlas: PBMCs from 12 donors stimulated with 90 cytokines plus controls, giving 1,080 paired baseline and post-perturbation scRNA profiles. They train a “Virtual Instrument” that takes a baseline donor embedding and a cytokine protein embedding (from ESM2) and predicts a perturbed donor embedding, which is then decoded back to cell embeddings and finally to gene expression. They evaluate in three challenging regimes: unseen cytokines, unseen donors, and unseen donor–cytokine pairs. At the donor-embedding level, they compare against a linear regression operator and several mean-based heuristics (donor-conditioned mean, cytokine-conditioned mean, and a global pooled mean). At the cellular and expression levels, they compare distributions using Wasserstein distance between predicted and observed post-perturbation cell embeddings, and correlation of gene-level fold changes, respectively. Across unseen-donor and unseen donor–cytokine regimes, PULSAR consistently outperforms all baselines: it achieves substantially lower RMSE in donor space, smaller Wasserstein distances in cell space, and higher correlations for differentially expressed genes, capturing individualized and lineage-specific cytokine responses that simple averaging or linear models cannot.

While useful, there are still limitations and clear next steps from this paper. As in most modeling problems, the authors note that fully end-to-end learning across molecular, cellular, and donor levels would be ideal, but is not computationally tractable here, which is why the model relies on information extracted from pre-trained foundation models at lower levels. Pseudobulk seems like a reasonable baseline and performs within a similar range to PULSAR embeddings, albeit consistently worse, but there are other models and efforts in the field that directly tackle “bag-of-cells to donor phenotype” prediction which are not discussed or compared against here, such as CloudPred, attention-based multiple-instance learning approaches, and scAGG. These methods already show that more structured cell-aware models can outperform pseudobulk, so including them would make the case for PULSAR’s incremental value stronger. Overall, PULSAR is a compelling step toward a multi-scale foundation model, but a more complete benchmarking story against existing immune profiling architectures will be important to understand exactly where its advantages come from and how much more information can be extracted from hierarchical representation learning.

Notable deals

Metri Bio emerges from stealth with $5M pre-seed round led by Pillar VC. The company is targeting treatments for endometrial diseases, citing the persisting disparity in attention and treatments devoted to women’s health conditions such as endometriosis despite their prevalence—their press release cites that endometriosis alone affects 1 in 10 women. Existing treatments for endometrial disorders (like many women’s health indications) are often largely ineffective in the long-term or come with “intolerable side effects.” Metri’s 3D endometrial modeling technology was spun out of the Sozen Lab at Yale and allows access to novel biological mechanisms underlying endometrial diseases, directing development of first-in-class therapeutics for endometriosis and more. Funding from this round will support further discovery platform buildout, team expansion, and R&D as Metri moves toward preclinical studies and beyond. Other investors participating include: Pace Ventures, Slocum Management, Navec Investments, and several unnamed angels.

Protego Biopharma raised an oversubscribed $130M Series B led by Novartis Venture Fund and Forbion. The San Diego-based biotech specializes in small molecule drug discovery for disorders implicating protein misfolding, addressing this issue via utilization of a ‘unique pharmacological chaperone mechanism’ where small molecules guide proteins back into a correct conformation. The funds from this round will go toward progressing Protego’s lead candidate, PROT-001, through crucial clinical trials for treatment of AL amyloidosis, a debilitating rare disease that can cause severe damage of the heart and other organs, often resulting in fatalities. Should PROT-001 succeed in trials, it would mark “the first disease-modifying treatment for AL amyloidosis,” a potentially particularly remarkable accomplishment given the various previous biopharma candidates that have failed while chasing this aim. Other participants in the round include new investors: Omega Funds, Droia Ventures, YK Bioventures, and Digitalis investors as well as existing investors: Vida Ventures, MPM BioImpact, Lightspeed Venture Partners, and Scripps Research.

Regeneron inks $150M deal with Tessera Therapeutics for joint development of promising rare disease gene writing asset. Tessera’s TSRA-196 seeks to treat alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, a debilitating disease affecting 200,000 in the U.S. and Europe alone which results from a mutation in the serpina1 gene. This mutation prevents adequate supply of the alpha-1 antitrypsin protein which protects against damage to the liver and lungs—in severe cases, the protein may even misfold and accumulate in the liver resulting in toxicity and further exposing the lungs to diseases such as COPD and emphysema. Developed through Tessera’s proprietary Gene Writing program, TSRA-196 offers a possibility of one-time treatment to correct the mutation and is expected to enter into IND by year end. The deal includes upfront cash and equity investment of $150M with the potential for up to $125M in milestone payments for Tessera. It also confers a codevelopment structure in which Tessera leads first-in-human trials and Regeneron handles following commercialization and global development.

Akura Medical secures first close of a $53M Series C led by Qatar Investment Authority.A portfolio company of Shifamed, the medtech company is seeking to revolutionize care for venous thromboembolism (VTE), a condition that affects up to 900,000 people in the U.S. alone where it is a leading cause of cardiovascular death.Akura’s central technology is the Katana™ Thrombectomy System, which is comprised of a sophisticated funnel that is able to carefully break up and remove clots attached to a sheath and catheter which feed live insights on clot engagement and clearance as well as blood drawn to The Sentinel™ console, reducing procedural uncertainty according to the company’s website. The system is further enabled by the company’s NavIQ™ quantification software which is “designed to convert a CT angiogram in a 3D model of the pulmonary vasculature” allowing for better anatomical visualization and navigation, informing presurgical planning. Funds raised will be used for further tech buildout and QUADRA-PE clinical trial enrollment with regulatory submissions as well as setting up a joint venture in Qatar. Other existing investors participated in this round.

In case you missed it

Profluent Raises $106M to Scale Frontier AI Models for Programmable Biology

Scripta Therapeutics raises $12m to flip the script on drug discovery

Onepot AI raises $13M to help make chemical drug creation easier

OpenAI backs Red Queen Bio, a startup aiming to block AI-enabled bioweapons

Seqhub is partnering with JGI’s Antonio Camargo to Make Hyper-Prevalent Gut Microbes Discoverable

Novel LNP Delivers Influenza mRNA Vaccine at 100-Fold Lower Dose

Semantic design of functional de novo genes from a genomic language model

What we listened to

What we liked on socials channels

Field Trip

Did we miss anything? Would you like to contribute to Decoding Bio by writing a guest post? Drop us a note here or chat with us on Twitter: @decodingbio.