BioByte 132: Generating Novel Bacteriophages with Genome Language Models, DNA Aptamers for Fertility Tracking, Probabilistic Inference in Mice, and the Predictive Power of GEM-1 in Transcriptomics

Welcome to Decoding Bio’s BioByte: each week our writing collective highlight notable news—from the latest scientific papers to the latest funding rounds—and everything in between. All in one place.

What we read

Papers

Generative genomics accurately predicts future experimental results [Koytiger et al., bioRxiv, September 2025]

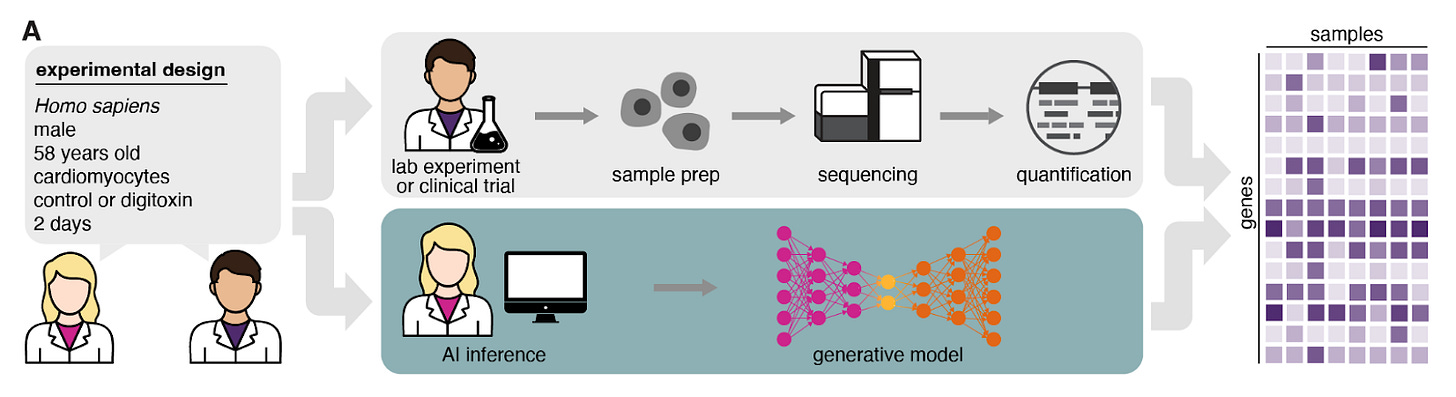

Why it matters: RNAseq profiles of different experimental types are laborious and expensive to acquire. Koytiger and Walsh et al. develop GEM-1, which leverages a deep latent-variable model trained on mined RNAseq data with LLM-cleaned metadata to enable scientists to generate specialized transcriptomic datasets in silico.

Transcriptomics foundation models have generally modeled the following question: given the expression levels of genes A–Y in my tissue/cell of interest, what is the likely expression level of Z? Variations of this framework have expanded toward incorporating other latent variables or experimental constraints. MrVI from Nir Yosef’s lab at UC Berkeley models variation between different scRNA samples with latent variables. GEARS from Jure Leskovec’s lab at Stanford models genetic perturbations as network-level perturbations on a baseline single-cell gene expression network. Researchers from Synthesize Bio see these steps and take a leap, attempting to model not just one covariate, but a full set of metadata factors—biological, technical, and perturbational—all at once in their model GEM-1. How does lupus affect the transcriptomic profile? GEM-1 can tell you. How does lorlatinib affect hypoxia-pathway gene expression? GEM-1 can tell you. How does the transcriptomic profile of a liver from a male taking TCDD compare to that of a healthy female? GEM-1 can also tell you. GEM-1 specializes in parameterizing metadata and learning to predict transcriptomic profiles from them to enable specialized transcriptomic queries.

How does it do this? Under the hood, GEM-1 is a deep latent-variable model that learns a likelihood over expression given three distinct latent embeddings. These are sourced from metadata-conditioned prior networks that turn the metadata into separate latent distributions capturing biological (e.g., sex, tissue, disease), technical (e.g., platform, library prep), and perturbational (e.g., drug or gene, dose, time) factors; when possible, perturbation identity is embedded with pretrained foundation models (for molecules/genes). A decoder expands the latent information in these embeddings into a full transcriptomic profile. Koytiger and Walsh et al. also enable what they call reference-conditioning: if you have a measured control sample in the exact biological/technical context (say, ear tissue with a particular assay), the expression encoder first infers biological+technical latents from that control; you then swap in a new perturbation latent and decode the counterfactual response. In practice, they find this boosts accuracy from pseudoreplicate-level in fully synthetic mode to exceeding pseudoreplicate reproducibility across all holdouts, and it specifically rescues novel biological contexts (e.g., new tissues/cell lines) where metadata alone is weak.

How did they train it? They first built a very large paired dataset of bulk RNA-seq expression + harmonized metadata from the SRA through June 30, 2024: 589,542 human samples identified, 44,592 genes quantified per sample, 470,691 samples from 24,715 datasets passing QC. They then used a metadata agent (LLM + biological databases) to convert raw, messy SRA fields into a controlled vocabulary describing tissues/cell types, diseases, and perturbations—spanning >18,000 distinct perturbations (including >650 small molecules and >300 pathogen infections). These paired expression/metadata records train GEM-1 end-to-end under an ELBO objective (reconstruction + KL to the metadata-conditioned priors).

On “future” experiments deposited after the training cutoff, GEM-1 in fully synthetic mode already reaches pseudoreplicate-level accuracy (comparable to cross-study lab repeats), and with reference conditioning it exceeds that bar across holdouts. They also synthesize GTEx-like and TCGA-like cohorts (GTEx/TCGA sequencing data from dbGaP were not used for training), and show that AI-generated samples cluster with the corresponding clinical cohorts and recapitulate expected molecular structure (e.g., tissue-of-origin, healthy vs. cancer, CMS subtypes). One key observation from the team is that ~95% of post-cutoff holdout experiments have perturbations/contexts already seen during training: much of the new data is in-distribution! In the rarer novel biological contexts (e.g., unseen tissues/cell lines) fully synthetic performance drops. However, tackling this seems tractable. First, they use one-hot categories to encode tissues—this approach is catastrophically unable to model out-of-distribution inputs. Just like how they leveraged foundation-model embeddings to model small molecule and genetic perturbations, ontology/text-based tissue embeddings could potentially reduce this out-of-distribution failure mode. Second, as public archives grow and metadata coverage improves, the model’s in-distribution envelope should expand, further enabling precise, metadata-conditioned “what-if” queries across the public transcriptomic universe.

Discovery of high-specificity DNA aptamers for progesterone using a high-throughput array platform [Fujita et al., bioRxiv, September 2025]

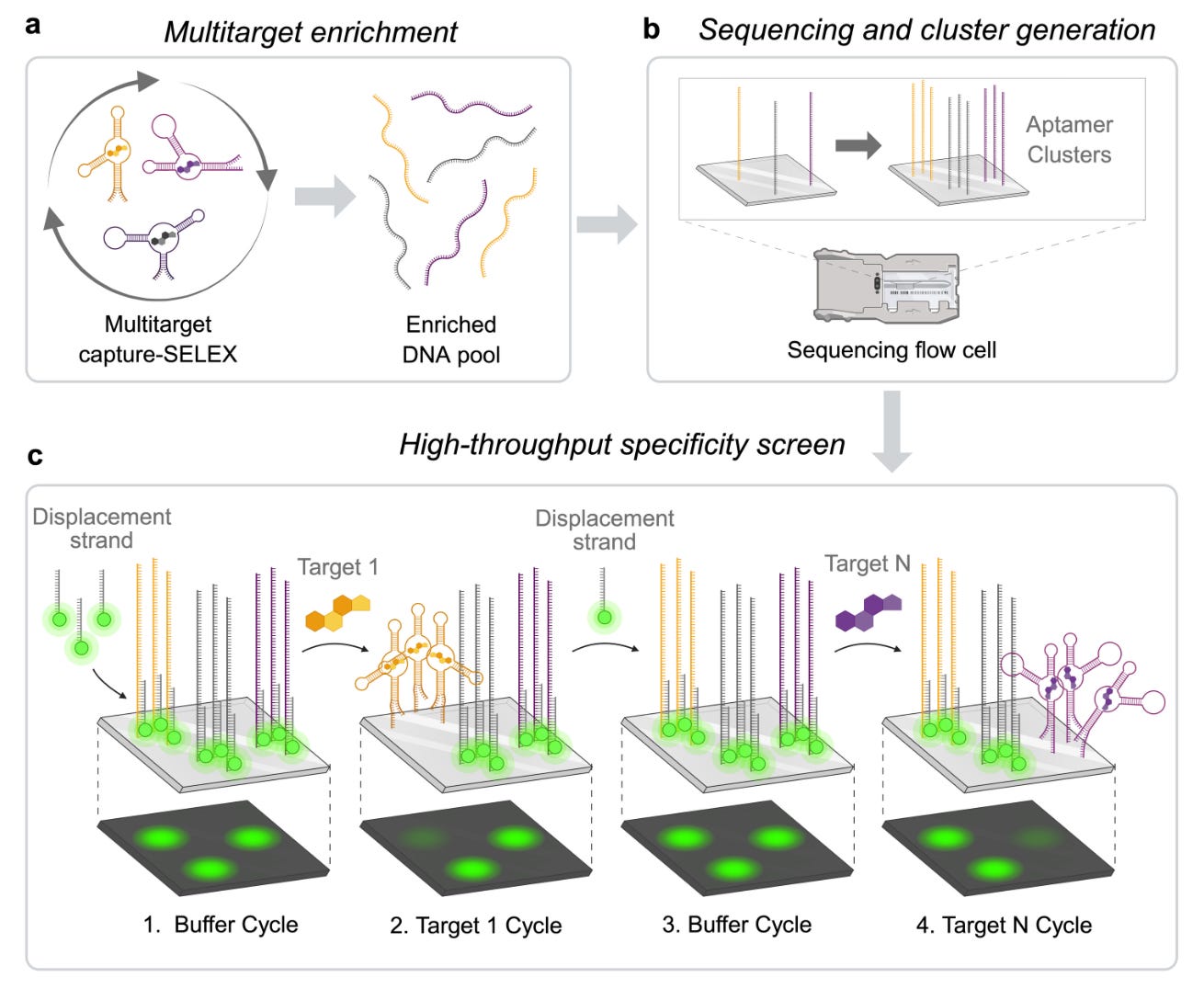

Why it matters: DNA aptamers, which are nucleic acid-based molecules that can bind targets with high affinity and specificity, have been challenging to develop into products that can distinguish between similar small molecule targets. In this paper, the authors found high-affinity, high-specificity DNA aptamers for progesterone, a hormone that is essential for fertility tracking and reproductive health management. This technology could be the foundation to create biosensors for such applications.

Tom Soh’s lab at Stanford released a new pre-print outlining the methodology by which they discovered DNA aptamers with high affinity and specificity for progesterone. The aptamer array platform can characterize millions of aptamers in a single experiment, allowing simultaneous profiling of affinity and specificity. By applying this platform to systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX), which is used for aptamer selection, the team was able to reduce the number of enrichment rounds by more than 50% (from 15 to 7).

The team previously found high-affinity, high-specificity DNA aptamers for tryptophan metabolites and in this paper they found ones for progesterone, without cross-reactivity with analogues such as estradiol. The two top candidates had sub 40mM KDs (dissociation constants) and negligible binding to non-targets.

Engineered prime editors with minimal genomic errors [Chauhan et al., Nature, September 2025]

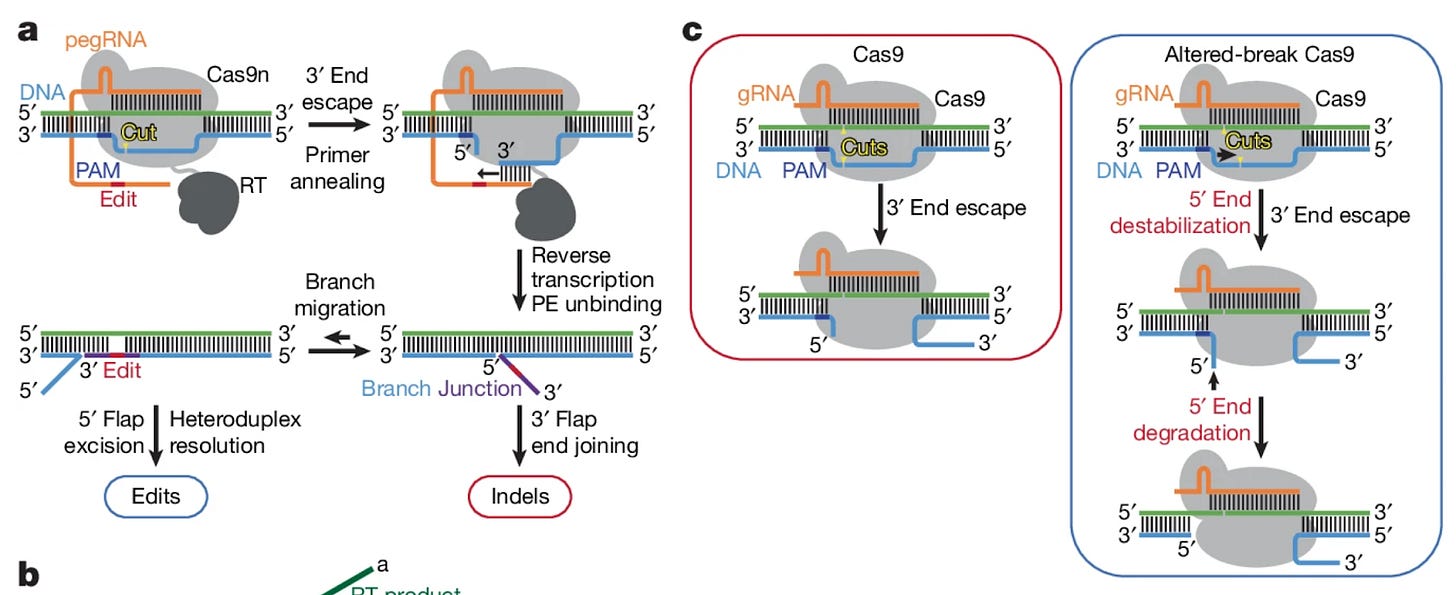

Why it matters: Prime editors have emerged as a supremely powerful class of genome editors, capable of carrying out insertions, deletions, and substitution edits in DNA without requiring double-stranded breaks. However, the technology is still prone to insertion and deletion errors during the editing process which potentially undermine its overall effectiveness. In this paper, the authors focus on the competition between the 3’ end of the nicked strand compared to the tightly bound 5’ end as a reason for indel errors and propose mutating the Cas9-DNA interface to promote binding of the edited strand. This rational design approach demonstrates a significant reduction in indel errors and paves the way to improve the accuracy of other prime editors.

Prime editors use an extended guide RNA (pegRNA) to guide a Cas9 nickase and reverse transcriptase to the desired editing site. After the nickase makes a single-stranded break, the nicked 3’ end anneals with the pegRNA template and allows the reverse transcriptase to add the desired edit into an extension of the strand. Afterwards, the edited 3’ strand competes to displace the 5’ strand to finally incorporate the edit. It is this inter-strand competition that is a primary source of indel errors, specifically because the 3’ strand is not exactly complimentary and can also escape from being bound by the Cas9 in contrast to the 5’ strand. To “even the playing field” between the two competing strands, the authors investigate how mutations to the nickase may alter the position of nicked end induction and promote 5’ strand degradation.

The authors began by measuring how mutations to Cas9 affected nick positioning and DNA end stability. Specifically, it was found that a range of alanine substitutions at various positions altered nick positioning but most importantly prompted increased degradation of PAM-side DNA ends. This evidence led the team to probe the same mutations within full prime editors (rather than just the Cas9). Mutated PE variants demonstrated significant reductions in indel errors, as well as generally improved negative:positive edit ratios marking a boost in overall efficiency. The most effective PE was able to achieve edit:indel ratios as high as 361:1 in the presence of mismatch repair (MMR) inhibition. While the most error-free PE variant showed great promise, its performance came at the expense of decreased editing efficiency. To combat this, the authors adopted a rational design approach and tested the effect of select Cas9 mutations on editing activity. Certain mutations were found to increase Cas9 activity in isolation, while others were shown to decrease the formation of double-stranded break formation. The final optimized candidate, known as extra-precise prime editor (xPE), was found to improve edit:indel ratios from 276:1 from the most effective nick-position-relaxed PE to 354:1.

This work demonstrates the effectiveness of targeting optimization strategies to improve the efficacy of prime editors. Continued reductions to the indel error rate and improvements in overall efficiency will certainly pave the way for more widespread adoption of the technology across a range of gene editing applications. It will be interesting to see how alternative approaches to optimizing the Cas9 enzyme function and guide RNAs with a mix of in silico and experimental assays may yield further improvements in prime editor function and safety.

Generative design of novel bacteriophages with genome language models [King et al., bioRxiv, September 2025]

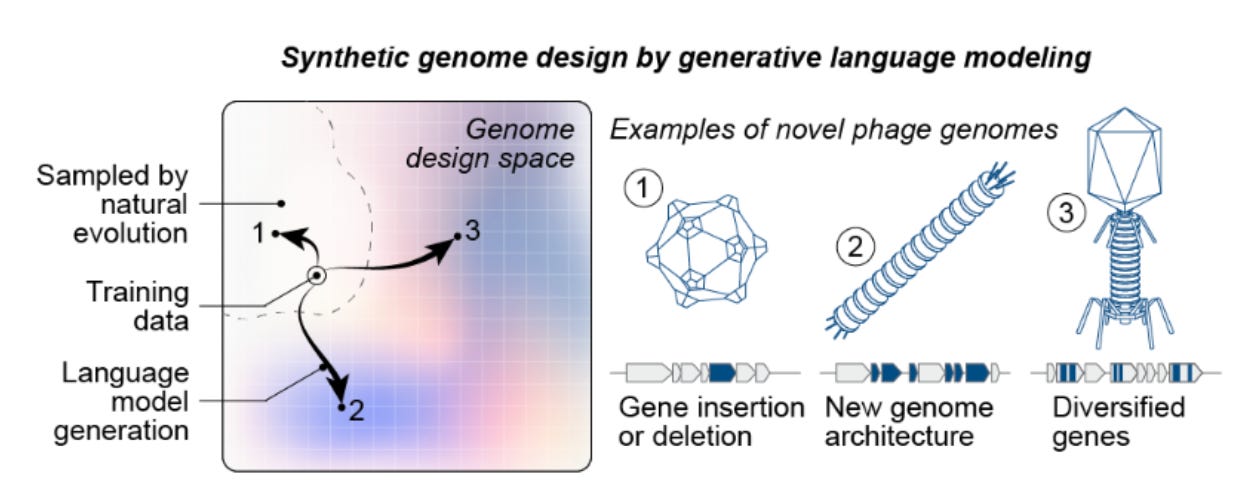

Why it matters: Generative models have evolved – from designing proteins to engineering entire, functional genomes. King et al. demonstrate that genome language models—when finetuned and carefully paired with biological filters—can produce novel ɸX174 bacteriophages that are viable and exhibit higher fitness than their natural counterparts. They diverge in genomic similarity from natural phages to the extent that they can be classified as a new species. Given the sheer fragility and complexity of long-range interdependencies in genomes, this shifts genome design from bespoke, human-driven craft to a data-driven exploration of sequence space, holding deep implications for synthetic biology.

The team of researchers from Arc Institute and Stanford University blended model creativity with hard biological constraints to achieve this. Their approach began by fine-tuning Evo models (genome language models trained on 9.3 trillion nucleotides spanning all domains of life) on ~15,000 Microviridae genomes, the viral family of ɸX174. Candidate ɸX174 bacteriophage sequences were then generated using a short consensus sequence from ɸX174-like genomes as a template prompt. Subsequently, they applied a filtering workflow to extract promising genomes by enforcing constraints on sequence quality, host tropism (spike protein similarity and gene annotation comparisons to ɸX174), and evolutionary diversity. This last step was crucial for systematically selecting novel sequences by filtering for specific gene counts, gene arrangements (synteny), and low protein sequence identity to avoid simple duplicates of ɸX174. This finetuning and filtering workflow is essential for identifying high-signal genomes, as the base Evo 1 and 2 models initially produce sequences where only 19-38% were classified as viral.

From thousands of initially generated sequences, the team curated 302 candidates and synthesized 285 genome assemblies. By transforming the assembled genomes into E. coli, they recovered 16 viable (E. coli growth-inhibiting) phages. While the hit rate is modest, the viable designs are not trivial retreads of nature: many exhibit low nucleotide BLAST recall, protein amino acid identities down to ~63%, and conserved coding density while introducing large, structural rearrangements. For multiple Evo phages, their average nucleotide identity to known natural counterparts sinks below 95% —meeting the genomic criteria to be classified as a separate species. As expected, these novel phages displayed phenotypic diversity. In competitive growth assays, some isolates outcompeted both the wild type and other generated phages by 16–65x in relative population growth, while others demonstrated faster lysis kinetics (lysis speed was not the sole determinant of fitness in their experiments).

Structural analysis provided deeper validation that the model learns context-aware co-variation not just memorized motifs. In Evo-ɸ36, the gene for its pilot protein (gene J) is homologous to a distant Microviridae virus (G4). Despite this, cryo-EM and AlphaFold3 structures show that the G4-like J-protein integrates compatibly into the ɸX174 capsid. This result implies the model internalized higher-order, co-evolutionary constraints rather than simply copying isolated protein motifs.

Furthermore, the researchers found that generative libraries can seed evolvability: cocktails of Evo phages overcame two strains of ɸX174 resistant E. coli where wildtype ɸX174 failed. Interestingly, the two predominant Evo phage genomes responsible for overcoming resistance in each respective strain were genetic mosaics—formed through recombination of segments from 2-3 Evo phages in the cocktail, along with 1-2 novel point mutations. This illustrates that they can supply functional diversity and produce unique, adaptive solutions—a double-edged feature for therapeutic and biosafety reasons.

Looking ahead, this work raises substantive risks and opportunities. On the cautionary side, viability was rare (though richer in-silico fitness predictors can improve this), the work centers on a well-characterized scaffold and a non-pathogenic host, and a broader application to larger or eukaryotic viruses entails major DNA synthesis and biosafety hurdles. However, the tangible upside is clear: generative design can accelerate discovery of host-range variants, create diverse therapeutic phage pools, and serve as an experimental probe for genome-level epistasis and assembly constraints. Ultimately, this paper establishes a robust foundation for genome design, and opens up new avenues for sampling, exploring, and steering biology with AI—especially as interfaces for conditioning and controlling model generation develop. In short, AI is proving to be a powerful design substrate for biology.

Brain-wide representations of prior information in mouse decision-making [Findling et al., Nature, September 2025]

Why it matters: This work is one of the first brain-wide, cellular-resolution investigations of how priors are encoded during decision-making. By showing that prior information is represented broadly, not confined to classical “decision” regions, the findings support the idea that the brain operates more like a large Bayesian network, where inference is distributed and recurrent across sensory, motor, and associative circuits. This matters because it challenges simplified, hierarchical views of cognition and points to a richer, network-level implementation of probabilistic reasoning.

Probabilistic inference and the use of priors are often described as key mechanisms of human and animal reasoning, yet how our brains actually encode such priors has remained unclear. Competing views suggest that prior information is integrated only in high-level decision areas, or alternatively, that such inference is a brain-wide property involving loops across many regions. To test this, researchers from the International Brain Laboratory trained mice on a visual decision-making task with changing prior probabilities and recorded activity across hundreds of brain areas using Neuropixels probes and wide-field calcium imaging. They found mice learned to estimate these priors based on previous actions and that the neural signatures of the subjective prior were present in nearly all levels of processing in the brain, supporting the idea of widespread multidirectional inference.

Notable deals

Lila Sciences raised a $235M Series A co-led by Braidwell and Collective Global. The company’s mission is to build “scientific superintelligence” under the belief that AI can execute along the entirety of the scientific method, significantly expediting critical discoveries spanning medicines and diagnostics, materials and manufacturing, compute and energy. Lila’s press release describes their pursuit as constructing an operating system for autonomous science, unifying AI, software, and robotics to create a closed-loop end-to-end platform where AI is able to conduct experiments at scale in a controlled environment. This new funding will fuel the company’s next phase of growth, enabling Lila to commercialize its platform and partner with biopharma companies to dramatically cut discovery timelines and increase success rates. The biotech also announced the opening of several new locations in Boston, San Francisco, and London. Other participants in the round / existing investors include: Altitude Life Science Ventures, Alumni Ventures, ARK Venture Fund, Common Metal, Flagship Pioneering, General Catalyst, March Capital, the Mathers Foundation, Modi Ventures, NGS Super, the State of Michigan Retirement System, and a wholly owned subsidiary of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA).

Ollin Biosciences launches with a $100M financing round led by ARCH Venture Partners, Mubadala Capital, and Monograph Capital. A clinical-stage biopharma, Ollin’s focus centers on accelerating the development of ophthalmological therapeutics targeting vision-threatening diseases. The company’s lead program, OLN324, a VEGF/Ang2 bispecific antibody, is in the midst of Phase 1b clinical trials for treating wet (neovascular) age-related macular degeneration (wAMD) or diabetic macular edema (DME), two leading causes of vision degeneration in elderly populations. OLN324 delivers a higher molar and higher potency dose of the designated antibody and is in competition with Genentech’s existing faricimab for best-in-class designation for treatment of the aforementioned disorders. Ollin has several other substantially-developed candidates, with its second program, OLN102, which is intended to treat thyroid eye disease (TED) and autoimmune components of Graves’ Disease, slated to enter clinical development in 2026.

Dualitas emerges from stealth with $65M Series A co-led by Versant Ventures and Qiming Venture Partners USA. The funding will be used to advance the development of Dualitas’ portfolio of next-generation bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) as well as the company’s proprietary BsAb discovery engine, DualScreen. Their two lead programs—for autoimmune diseases (DTX-102) and allergic diseases (DTX-103)—are currently in lead optimization, with four other announced programs earlier in development. The round also included participation from founding investor, SV Health, as well as new investors: Chugai Venture Fund, Eli Lilly, and Alexandria Venture Investments.

Novartis continues partnership with Monte Rosa Therapeutics with a second deal which could total up to $5.7B.This doubling down on their partnership nets Monte Rosa $120M upfront in exchange for the application of their AI/ML-enabled QuEEN product engine towards the creation and optimization of new molecular glue degraders (MGD) against undisclosed targets. For Monte Rosa, the deal also provides sufficient funding to continue to develop the remainder of their pipeline. The prior agreement centered on MRT-6160, a VAV1 degrader soon to be entering Phase II clinical trials in multiple immune-mediated diseases. The original deal also gave Novartis the rights to any other VAV1 degraders the company might design.

What we liked on socials channels

Events

Decoding Bio is coming to Boston on September 22! Start-up builders, pharma partners, and other contributors to the AI x Bio community will convene in Boston for an evening of networking and a panel discussion featuring speakers from Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, and Digital Biology. Sponsored by Orrick, Nova Rain Capital, Diffuse Bio, and CAC Group.

Note: This event has already reached maximum capacity, but you may apply to express interest in future Boston events here.

Field Trip

Did we miss anything? Would you like to contribute to Decoding Bio by writing a guest post? Drop us a note here or chat with us on Twitter: @decodingbio.